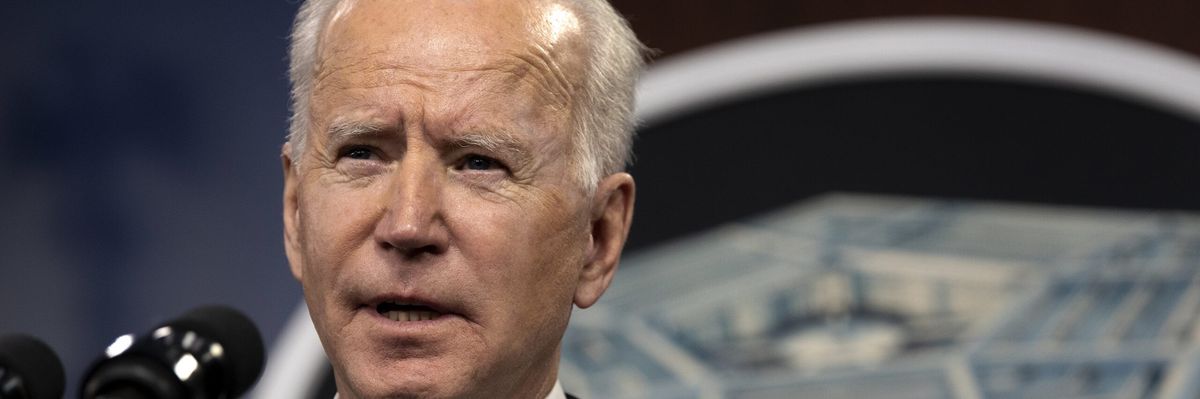

President Biden grabbed headlines on Tuesday when he declared in a speech to the United Nations General Assembly that the United States is “not seeking — I’ll say it again — we are not seeking a new Cold War or a world divided into rigid blocs.” Although China was never once mentioned by name, references to it were littered throughout the speech, and Biden reiterated Washington’s commitment to cooperating on shared challenges like climate change and preventing “responsible competition” from tipping into “conflict.”

Coming straight from the mouth of the American president in such a high-profile setting, this was a powerful statement that earned praise from many. But if Biden genuinely believes what he says, this betrays that he does not seem to understand the “new Cold War” at all, nor why cooperation and avoiding conflict cannot simply be spoken into existence.

It should be self-evident that neither Washington nor Beijing want a “new Cold War” simply for its own sake. The post-70s era of engagement largely kept the peace and helped mint more millionaires and billionaires on both sides than perhaps any other similar period in human history. Relations have deteriorated since that temporary lull of euphoria because the rise in China’s power has brought to bear contradictions in the two sides’ conception of their interests that always existed, but Beijing could do little about. And both have come to the conclusion that these interests are ultimately more important than a healthy relationship, and decided that securing the former is worth sacrificing the latter.

Thus, when Biden says he does not seek a “new Cold War” without outlining the specific steps he would take to actually avoid it, all he is doing is reiterating Washington’s longstanding position that relations can return to their healthier state so long as this happens on its own terms. If Beijing chooses to ignore these terms, the “new Cold War” will continue in perpetuity until it can afford to ignore them no longer.

What exactly are Washington’s terms? Biden will keep tariffs and sanctions in place, and continue to add additional rounds, until Beijing changes its tune on trade and human rights in Hong Kong and Xinjiang. The militarization of the Asia-Pacific will continue apace until the balance of power is resecured in Washington’s favor and Beijing backs down on Taiwan and the South China Sea, and then ultimately resigns itself to the reality of a permanent American military presence in its own backyard. So long as the Communist Party remains in charge, Beijing will not be allowed to exercise too much influence domestically or in international institutions, benefit fully from American technology or educational exchange, or wield its economic power to secure political influence.

Other than possible compromises on trade, these are, of course, terms that Beijing will not accept, and that the Communist Party and Xi Jinping cannot accept. In fact, Beijing has made its negotiating position very clear, going so far as to present it in list form to Deputy Secretary of State Wendy Sherman during her visit to China in July; taken together with Beijing’s “three red lines,” they represent, in effect, a complete, across-the-board rebuke of Washington’s position. To the best of my knowledge, I have never once heard a U.S. official reference or discuss these lists or red lines, despite the fact that over the two preceding months several top Chinese officials have repeatedly reiterated their importance for the health of the relationship and cooperation on issues such as climate change.

Holding up the climate as hostage seems like something a mob boss would do. But Beijing believes its terms are evidently reasonable, and not equivalent to Washington’s: stay out of our domestic affairs, and keep your military out of our backyard and as far away as possible. It asks that if Washington cannot accept these terms as the basic foundations of any healthy and balanced relationship — it should be noted that Washington expects Beijing to abide by these same principles regarding its own affairs and backyard — then why is China considered the one blocking cooperation?

Both sides, no matter what Biden and his administration might say, have concluded that their interests and current negotiating position are more important than cooperation. Unless one side or the other buckles, this will be a problem that will plague cooperation and other forms of collaboration for the foreseeable future, and will not disappear simply because Biden said some forceful and convincing words into a microphone.

Biden’s claim that Washington does not seek a world “divided into rigid blocs” is even more deserving of derision, coming as it does less than a week after Washington announced the formation of just such a bloc aimed directly at China in AUKUS. But the reasons stretch well beyond last week or even the Biden or Trump administrations, and cut to the core of what serves as perhaps the most insurmountable divide between the two sides.

Beijing has long perceived the current security architecture in Asia, the “hub-and-spokes” alliance system — based on separate bilateral defense treaties between the United States and Japan, South Korea, Australia, the Philippines, and Thailand — as a bloc that is rooted in American power. As National Security Council China director Rush Doshi outlines in his new book, Beijing long feared that the “China threat” theory would allow Washington to turn this security order on China as it rose and sought to exercise greater influence; in fact, this is the only logical target this this alliance system could conceivably be aimed at.

In other words, Washington has become so inebriated by the fact of American hegemony that it forgot it had already divided the world into blocs. And these blocs are, in fact, rigid ones: it is effectively political suicide for anyone in Washington to cast askance at, let along advocate for the abrogation of, the American alliance system, and Beijing can certainly not be allowed to challenge it.

But the reality is that, were the shoe on the other foot, Washington would never accept the degree of strategic vulnerability that it asks of Beijing. If China had a series of alliances and bases scattered across the Americas and at particular points surrounding the continental United States, regardless of their historic or geopolitical justifications, absolute pandemonium and mayhem would break out in Washington. The most chauvinistic elements of American politics would be empowered and the country would be set on a permanent war footing. From this position, Washington would believe itself justified in using whatever dirty and ugly tactics might be necessary to secure its interests. It would do so regardless of how they might violate international law or basic norms of interstate relations, just as Beijing has done in the South China Sea, in cyberspace, and through economic coercion aimed at Australia and South Korea, among others.

As revelations about calls between Joint Chiefs Chairman General Mark Milley and other U.S. officials and their Chinese counterparts in the waning months of the Trump administration make clear, managing U.S.-China military competition, which is only just starting to really heat up, will be an incredibly difficult task. Of course, neither side wants to go to war. But neither will they fully be in control of the forces that might accidentally spark it; Biden says competition cannot be allowed to lead to conflict, but he does not want to take any of the steps that would actually make it less likely. In other words, he wants to have his cake and eat it too.

Ultimately, it is the fundamental gap in perceptions between the two sides — with both Washington and Beijing believing they are the reasonable party, and the other the one who started it — that was laid bare for all to see in Biden’s speech. This gap defines the “new Cold War” itself, and is what will ensure it continues for some time. Anyone with experience working on Chinese foreign policy should be intimately familiar with these dynamics, and the fact that Biden and his China team apparently are not should be a major cause for concern.

It is very easy and tempting, both politically and intellectually, to simply throw one’s hands up and say that Beijing is asking for and deserves confrontation, so let’s just give it to them. It is hard to come to grips with the fact that this is not a real solution to the problems created by China’s rise, and even harder to find an alternative path forward. It is ultimately up to Washington to be the responsible party and choose to take that harder path; no one else is willing or able to do so, least of all Beijing. Until that day of reckoning comes, the new Cold War is here to stay, no matter what Biden might tell himself.